Hi friends,

As I studied the Sermon on the Mount, I also started to carefully read commentaries on the rest of the Gospel of Matthew.

Recently, I started to pay detailed attention to the genealogy in chapter 1.

Here are two interesting conundrums from the genealogy.

First, in verses 7-8, most English translations read, “…Abijah fathered Asa, Asa fathered Jehoshaphat…”

But if you look at the Greek text of the passage in Nestle-Aland 28, you see this:

I’ve underlined the important word - it reads “Asaph” - the Psalmist.

Likewise, in verse 10, most English translations read, “…Manasseh fathered Amon, Amon fathered Josiah…”

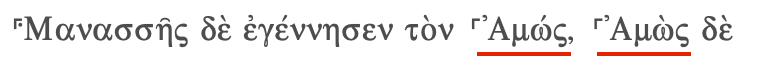

But in the Greek text, we have:

The name here is “Amos” - the prophet.

The question is: why does Matthew place Asaph and Amos in the genealogy of Jesus?

Dr. J. Richard Middleton offers this explanation:

The sum of all the numerical values of the fourteen names—as Matthew spells them—in the list from David to the exile is 560. This is exactly the number we get when we multiply the numerical value of David (14) with Jeconiah (40), the last king listed; this accounts for Matthew’s variant spellings of the names, including Asaph and Amos. While this playing with numbers might seem to contemporary readers as an unnecessary quirk (he could make his points without it), it is another way in which Matthew reinforces his desire to keep the name David before us. If the genealogy of Abraham to David suggests great possibilities for Israel, the genealogy of “from David to the deportation to Babylon” (Matt 1:17) affirms that these possibilities were squandered by the monarchy, beginning with David himself.

Middleton’s explanation of the genealogy relies heavily on discerning how Matthew used gematria - assigning numeric values to names based upon the letters within them - to make theological points.

What is at stake if we accept that Matthew used gematria, rather than historical precision, as his organizing principle for the genealogy?

At a minimum, that interpretation requires us to open our minds to the possibility that Matthew wrote from a very different perspective than our own starting point, which prizes historical exactness and accuracy.

James Snapp offers a sharply different explanation. He argues that in the original text, Matthew did write “Asa” and “Amon”, because it would be inconceivable for him to substitute the names of a well known Psalmist and Prophet into a list of kings for his audience. However, a later scribe made a copying mistake, leading to the manuscripts showing Matthew as using Asaph and Amos. As he puts it:

What has happened, I suspect, is that an early Western scribe, unfamiliar with Old Testament chronology, introduced the names of Asaph and Amos as a primitive attempt to pad Jesus’ Messianic résumé, so to speak, by adding prophets among his ancestry. The tampering of this scribe influenced the Western transmission-line represented by some Old Latin copies. When these Western readings intersected with the Alexandrian transmission-line, they blended into a crowd of orthographic variations – that is, in some Western Old Latin copies, and in Egypt, the names of Asaph and Amos were assumed to be variant-spellings referring to Asa and Amon, and for that reason, they were not corrected. Elsewhere, though, these readings were either never encountered, or were almost always rejected as variants which Matthew had not written and which he had been highly motivated not to write.

From another perspective, the Bible Project team argues that Matthew mentions Asaph and Amos as a “wink” to his audience that Jesus’ “family line” includes every part of the people of God - kings, prophets, and psalmists. They write:

For example, he changed the names of Asa and Amon to Asaph (the poet featured in the book of Psalms) and Amos (the famous prophet). Matthew is winking at us here, knowing that his readers would spot these out of place names. The point, of course, is that Jesus doesn’t just fulfill Israel’s royal hopes, but also the hope of the Psalms(Asaph) and the Prophets (Amos).

Dr. Craig Keener provides a similar perspective, stating,

Scholars have suggested that some ancient genealogies incorporated symbolic material based on the interpretation of biblical texts. Jewish interpreters of Scripture sometimes would modify a letter or sound in a biblical text to reapply it figuratively. Thus the Greek text of Matthew 1:10 reads “Amos” (the prophet) rather than “Amon” (the wicked king—2 Kings 21), and Matthew 1:8 reads “Asaph” (the psalmist) rather than “Asa” (a good king turned bad—2 Chron 16); most translations have obscured this point.

However, D.A. Carson challenges this interpretation, referring to the scholarship of Robert Gundry. He argues:

Robert Gundry suggests that Asaph is a deliberate change by Matthew to call up images of the psalmist (Pss 50, 73–83), as “Amos” … calls to mind the prophet. This is too cryptic to be believable. Orthography was not as consistent in the ancient world as it is today.

In other words, Carson’s perspective is that in Matthew’s time, names could have alternative spellings without too much concern or confusion.

While conceding that the precision of spelling names was different before computers, spell checkers, and the internet, it does seem that “Asaph” and “Amos” are glaringly different names than Asa and Amon.

Overall, it’s a confusing situation, reflected by the diversity and disagreements within the scholarship.

Have you heard a better interpretation?

Or, of these explanations, which one do you find most convincing?