Continuing the discussion from The "Compassionate" God in Exodus 34:

Kathleen, your question prompted me to ask how Buddhism understands compassion.

As I started to research this topic, I was reminded that every major religion has a diversity of expression, and there is no simple answer to this question.

For instance, writing at the Greater Good Science Center, Jennifer Goetz notes:

The more one reads Buddhist writings, the more one realizes that Buddhist compassion is similar to lay conceptions of compassion in name only. While lay concepts of compassion are of warm feelings for particular people in need, Buddhist compassion is not particular, warm, or even a feeling. Perhaps the most succinct and clear mention of this is in the discussions of the Dalai Lama and Jean-Claude Carriere (1996, p. 53). A footnote explains in refreshingly plain language that compassion in the Buddhist sense is not based on what we call “feeling”. While Buddhist’s do not deny the natural feelings that may arise from seeing another in need, this is not the compassion Buddhism values. Instead, Buddhist compassion is the result of knowing one is part of a greater whole and is interdependent and connected to that whole. It is the result of practiced meditations. Indeed, Buddhist compassion should be without heat or passion - it is objective, cold, constant and universal.

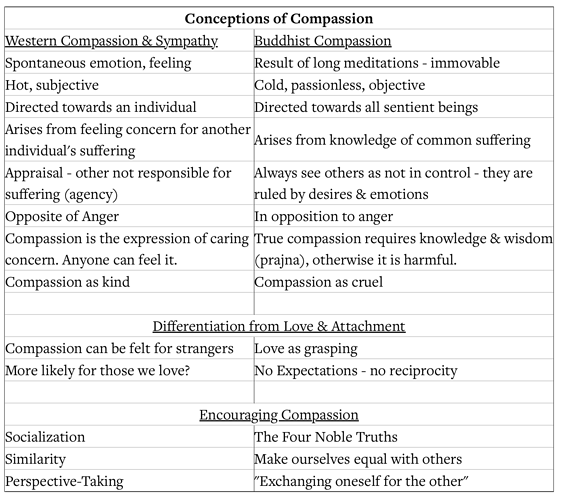

Here is her summary graphic:

According to Study Buddhism, Compassion is one of four immeasurable attitudes, and only one of two of them that is also limitless. It is defined as:

- Compassion – the factor that makes the heart quiver when others suffer and is the wish for the removal of their suffering. Its direct enemy is a cruel or harmful attitude (Pali: himsa). Its indirect enemy is grief, being emotionally overwhelmed by their suffering.

However, in the Nichiren tradition of Japanese Buddhism, notice the progression:

Further, immeasurable equanimity is the state of mind that is rid of the attitudes of immeasurable love, compassion, and joy. It is aware of others in such a way that it not only experiences neither happiness nor unhappiness, but is also neither attracted nor repelled by others. Thus, immeasurable equanimity parallels the fourth level of mental stability in that it is free of all feelings of unhappiness, physical and mental happiness, and the quiet joy of mental peace.

…

In Nichiren, the parallel with the fourth level of mental stability is much closer. There, immeasurable equanimity is a completely tranquil state of mind that is even-minded toward happiness and unhappiness, in all circumstances, such as when meeting friends and enemies. It is the state of mind that is rid of the attitudes of immeasurable love, compassion, and joy.

In the summary section we read,

Immeasurable compassion may include the wish that all limited beings:

- Be parted from suffering (the three kinds of suffering)

- Be parted from suffering and the causes for suffering.

This sounds good! However, Buddhists are also developing immeasurable equanimity. This part reads:

Immeasurable equanimity is a state of mind that includes being:

- Even-tempered toward all limited beings, in the sense of even when helping, not becoming too involved or not being indifferent, since ultimately everyone needs to reach liberation through his or her own efforts

- Completely tranquil and even-minded toward happiness and unhappiness, pleasure and pain, in all circumstances, such as when meeting friends and enemies, and is rid of the attitudes of immeasurable love, compassion, and joy

- Extending immeasurable love, compassion, and joy equally to everyone, without consideration of friends, enemies, or strangers

- Free of attachment, repulsion, and indifference toward others, and without feelings of some being close and others distant

- With the understanding that all limited beings are equal

- With the wish that all beings be equally benefited.

My tentative conclusion is that, to the degree that a specific form of Buddhism encourages freedom from attachment to others, this will affect how compassion is experienced as well.

I’m curious what others, with more experience of Buddhism, might say about this question.